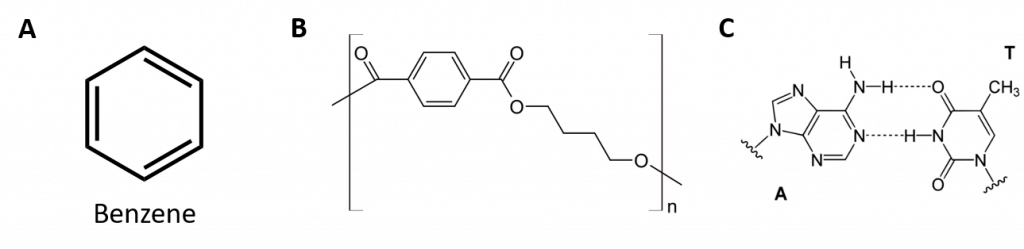

Aromatic hydrocarbons are defined by having 6-membered ring structures with alternating double bonds (Fig 8.2).

Figure 8.2: Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Aromatic hydrocarbons contain the 6-membered benzene ring structure (A) that is characterized by alternating double bonds. Ultradur, PBT is a plastic polymer that contains an aromatic functional group. The repeating monomer of Ultradur is shown in (B). Ultradur can be found in showerheads, toothbrush bristles, plastic housing for fiber-optics cables, and in automobile exterior and interior components. Biologically important molecules, such as deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA (C) also contain an aromatic ring structures.

Thus, they have formulas that can be drawn as cyclic alkenes, making them unsaturated. However, due to the cyclic structure, the properties of aromatic rings are generally quite different, and they do not behave as typical alkenes. Aromatic compounds serve as the basis for many drugs, antiseptics, explosives, solvents, and plastics (e.g., polyesters and polystyrene).

The two simplest unsaturated compounds—ethylene (ethene) and acetylene (ethyne)—were once used as anesthetics and were introduced to the medical field in 1924. However, it was discovered that acetylene forms explosive mixtures with air, so its medical use was abandoned in 1925. Ethylene was thought to be safer, but it too was implicated in numerous lethal fires and explosions during anesthesia. Even so, it remained an important anesthetic into the 1960s, when it was replaced by nonflammable anesthetics such as halothane (CHBrClCF3).

(Back to the Top)

8.1 Alkene and Alkyne Overview

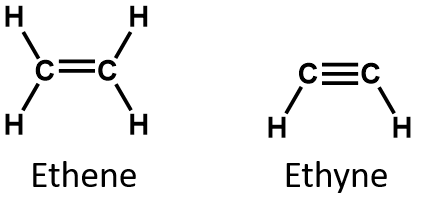

By definition, alkenes are hydrocarbons with one or more carbon-carbon double bonds (R2C=CR2), while alkynes are hydrocarbons with one or more carbon-carbon triple bonds (R-C≡C-R). Collectively, they are called unsaturated hydrocarbons, which are defined as hydrocarbons having one or more multiple (double or triple) bonds between carbon atoms. As a result of the double or triple bond nature, alkenes and alkynes have fewer hydrogen atoms than comparable alkanes with the same number of carbon atoms. Mathematically, this can be indicated by the following general formulas:

In an alkene, the double bond is shared by the two carbon atoms and does not involve the hydrogen atoms, although the condensed formula does not make this point obvious, ie the condensed formula for ethene is CH2CH2. The double or triple bond nature of a molecule is even more difficult to discern from the molecular formulas. Note that the molecular formula for ethene is C2H4, whereas that for ethyne is C2H2. Thus, until you become more familiar the language of organic chemistry, it is often most useful to draw out line or partially-condensed structures, as shown below:

(Back to the Top)

8.5 Geometric Isomers

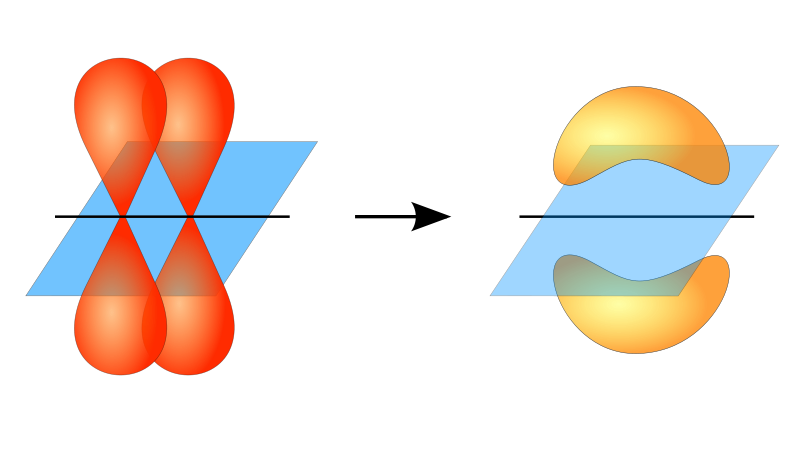

Within alkane structure there is free rotation about the carbon-to-carbon single bonds (C-C). In contrast, the structure of alkenes requires that the carbon atoms form a double bond. Double bonds between elements are created using p-orbital shells (also called pi orbitals). These orbital shells are shaped like dumbbells rather than the circular orbitals used in single bonds. This prevents the free rotation of the carbon atoms around the double bond, as it would cause the double bond to break during the rotation (Figure 8.7). Thus, a single bond is analogous to two boards nailed together with one nail. The boards are free to spin around the single nail. A double bond, on the other hand, is analogous to two boards nailed together with two nails. In the first case you can twist the boards, while in the second case you cannot twist them.

Figure 8.7 The formation of double bonds requires the use of pi-bonds. For molecules to create double bonds, electrons must share overlapping pi-orbitals between the two atoms. This requires the dumbbell-shaped pi-orbitals (show on the left) to remain in a fixed conformation during the double bond formation. This allows for the formation of electron orbitals that can be shared by both atoms (shown on the right). Rotation around the double bond would cause the pi orbitals to be misaligned, breaking the double bond.

Diagram provided from: JoJanderivative work - Vladsinger (talk)

The fixed and rigid nature of the double bond creates the possibility of an additional chiral center, and thus, the potential for stereoisomers. New stereoisomers form if each of the carbons involved in the double bond has two different atoms or groups attached to it. For example, look at the two chlorinated hydrocarbons in Figure 8.8. In the upper figure, the halogenated alkane is shown. Rotation around this carbon-carbon bond is possible and does not result in different isomer conformations. In the lower diagram, the halogenated alkene has restricted rotation around the double bond. Note also that each carbon involved in the double bond is also attached to two different atoms (a hydrogen and a chlorine). Thus, this molecules can form two stereoisomers: one that has the two chlorine atoms on the same side of the double bond, and the other where the chlorines reside on opposite sides of the double bond.

Figure 8.8 Alkene Double Bonds Can Form Geometric Isomers. (a) Shows the free rotation around a carbon-carbon single bond in the alkane structure. (b) Shows the fixed position of the carbon-carbon double bond that leads to geometic (spatial) isomers.

Click Here for a Kahn Academy Video Tutorial on Alkene Structure.

For this section, we are not concerned with the naming that is also included in this video tutorial.(Note: All Khan Academy content is available for free using CC-BY-NC-SA licensing at www.khanacademy.org )

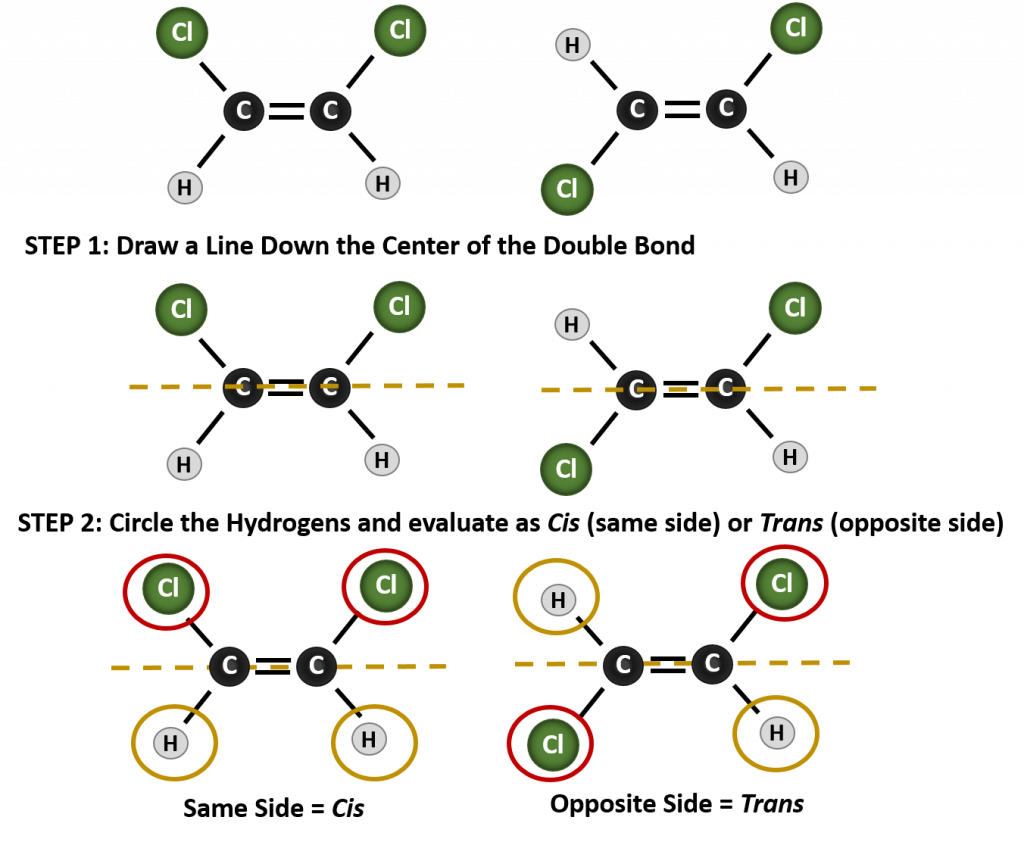

Cis-Trans Nomenclature

The cis-trans naming system can be used to distinguish simple isomers, where each carbon of the double bond has a set of identical groups attached to it. For example, in Figure 8.8b, each carbon involved in the double bond, has a chlorine attached to it, and also has hydrogen attached to it. The cis and trans system, identifies whether identical groups are on the same side (cis) of the double bond or if they are on the opposite side (trans) of the double bond. For example, if the hydrogen atoms are on the opposite side of the double bond, the bond is said to be in the trans conformation. When the hydrogen groups are on the same side of the double bond, the bond is said to be in the cis conformation. Notice that you could also say that if both of the chlorine groups are on the opposite side of the double bond, that the molecule is in the trans conformation or if they are on the same side of the double bond, that the molecule is in the cis conformation.

To determine whether a molecule is cis or trans, it is helpful to draw a dashed line down the center of the double bond and then circle the identical groups, as shown in figure 8.9. Both of the molecules shown in Figure 8.9, are named 1,2-dichloroethene. Thus, the cis and trans designation, only defines the stereochemistry around the double bond, it does not change the overall identity of the molecule. However, cis and trans isomers often have different physical and chemical properties, due to the fixed nature of the bonds in space.

Figure 8.9 A Guide for Determining Cis or Trans Conformations.

Click Here for a Kahn Academy Video Tutorial on Cis/Trans Isomerization

(Note: All Khan Academy content is available for free using CC-BY-NC-SA licensing at www.khanacademy.org )

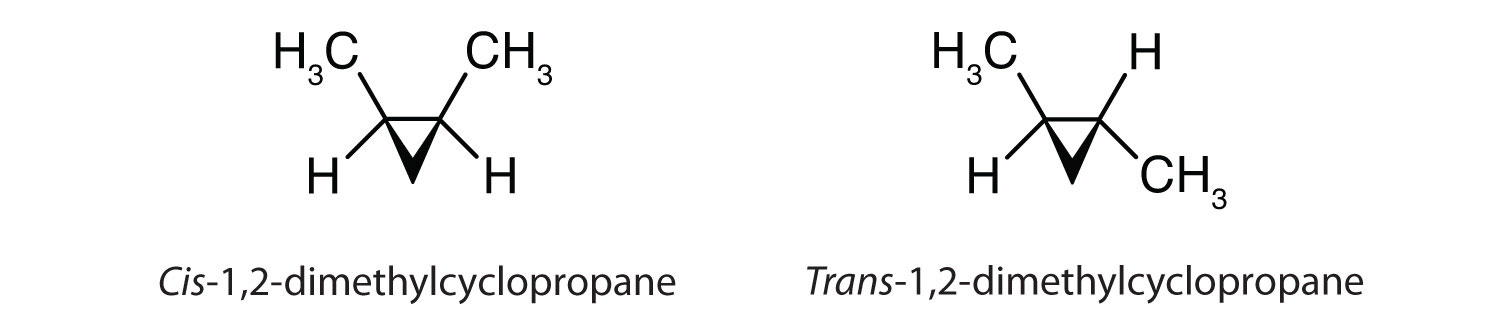

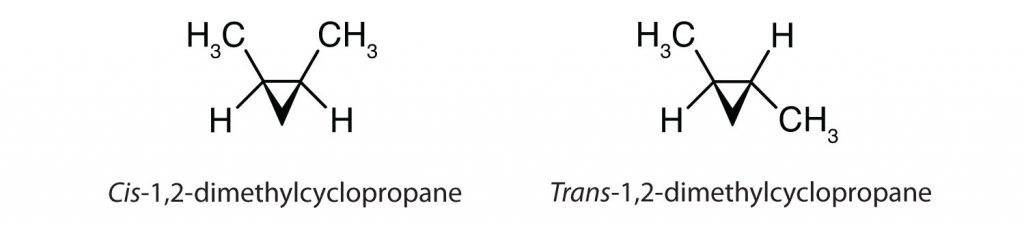

Cis-trans isomerism also occurs in cyclic compounds. In ring structures, groups are unable to rotate about any of the ring carbon-carbon bonds. Therefore, groups can be either on the same side of the ring (cis) or on opposite sides of the ring (trans). For our purposes here, we represent all cycloalkanes as planar structures, and we indicate the positions of the groups, either above or below the plane of the ring.

To Your Health

Possibly the most common place that you will hear reference to cis-trans conformations in everyday life is at the supermarket or your doctor’s office. It relates to our consumption of dietary fats. Inappropriate or excessive consumption of dietary fats has been linked to many health disorders, such as diabetes and atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease. So what are the differences between saturated and unsaturated fats and what are trans fats and why are they such a health concern?

Figure 8.10 Common Sources of Dietary Fats.

Photo from: TyMaHe

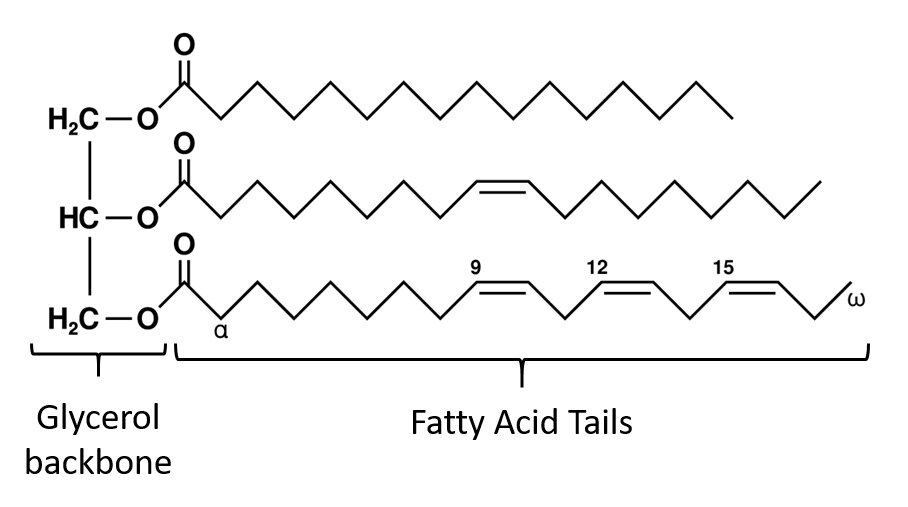

The most common form of dietary fats and the main constituent of body fat in humans and other animals are the triglycerides (TAGs). TAGs, as shown in figure 8.10, are built from one molecule of glycerol and three molecules of fatty acids that are linked together by an ester bond. In this section, we will focus on the structure of the long fatty acid tails, which can be composed of alkane or alkene structures. Chapter 10 will focus more on the formation of the ester bonds.

Figure 8.11. Example of a Triglyceride (TAG) Structure. Notice that each triglyceride has three long chain fatty acids extending from the glycerol backbone. Each fatty acid can have different degrees of saturation and unsaturation.

Structure adapted from: Wolfgang Schaefer

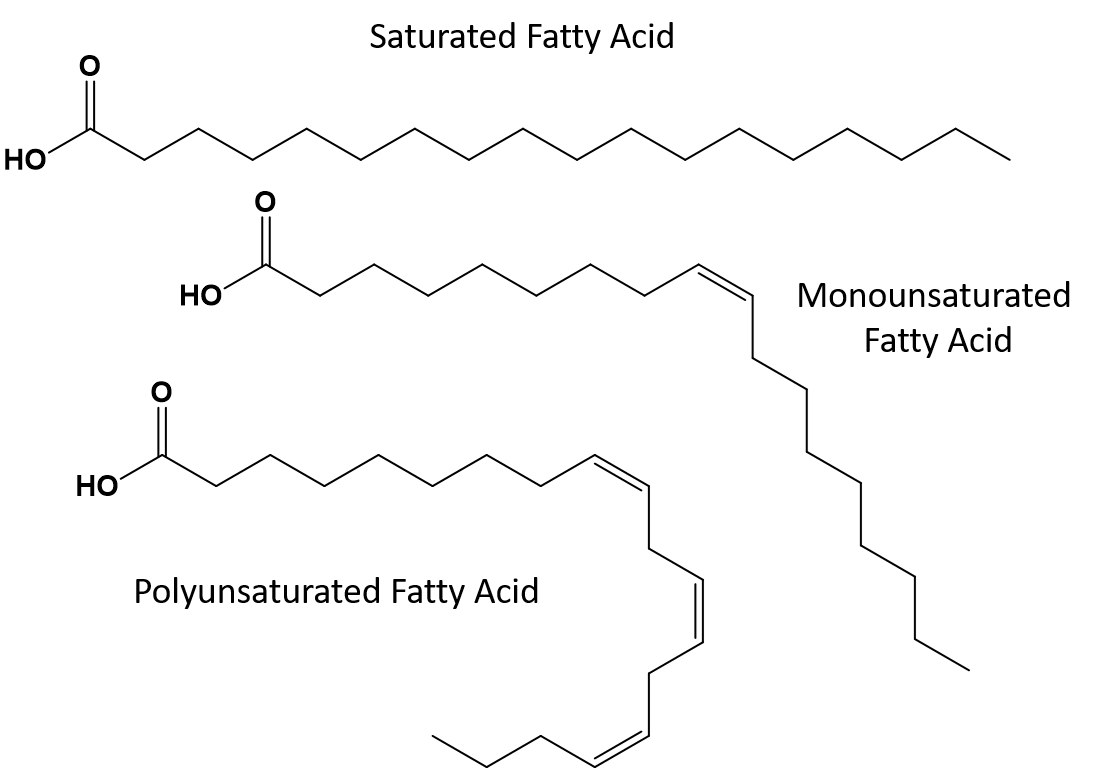

Fats that are fully saturated will only have fatty acids with long chain alkane tails. They are said to be ‘saturated‘ with hydrogen atoms. Saturated fats are common in the American diet and are found in red meat, dairy products like milk, cheese and butter, coconut oil, and are found in many baked goods. Saturated fats are typically solids at room temperature. This is because the long chain alkanes can stack together having more intermolecular London dispersion forces. This gives saturated fats higher melting points and boiling points than the unsaturated fats found in many vegetable oils.

Most of the unsaturated fats found in nature are in the cis-conformation, as shown in Figure 8.11. Note that the fatty acids shown in Figure 8.11 are drawn for convenience, so that they are easy to look at and do not take up too much space on the paper, but the bond angles written do not adequately portray the true spatial orientation of the molecules. When the fatty acids from the TAG shown in Figure 8.11 are drawn with correct bond angles, it is easy to see that cis-double bonds cause bends in the alkene chain (Fig. 8.12).

Figure 8.12 Cis-Double Bonds Cause Bends in Fatty Acid Structure

Thus, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats cannot stack together as easily and do not have as many intermolecular attractive forces when compared with saturated fats. As a result, they have lower melting points and boiling points and tend to be liquids at room temperature. It has been shown that the reduction or replacement of saturated fats with mono- and polyunsaturated fats in the diet, helps to reduce levels of the low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) form of cholesterol, which is a risk factor for coronary heart disease.

Trans-fats, on the other hand, contain double bonds that are in the trans conformation. Thus, the shape of the fatty acids is linear, similar to saturated fats. Trans fats also have similar melting and boiling points when compared with saturated fats. However, unlike saturated fats, trans-fats are not commonly found in nature and have negative health impacts. Trans-fats occur mainly as a by-product in food processing (mainly the hydrogenation process to create margarines and shortening) or during cooking, especially deep fat frying. In fact, many fast food establishments use trans fats in their deep fat frying process, as trans fats can be used many times before needing to be replaced. Consumption of trans fats raise LDL cholesterol levels in the body (the bad cholesterol that is associated with coronary heart disease) and tend to lower high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (the good cholesterol within the body). Trans fat consumption increases the risk for heart disease and stroke, and for the development of type II diabetes. The risk has been so highly correlated that many countries have banned the use of trans fats, including Norway, Sweden, Austria and Switzerland. Within the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently passed a measure to phase out the use of trans fats in foods by 2018. This measure is estimated to prevent 20,000 heart attacks and 7,000 deaths per year.

Figure 8.13 Structural differences in saturated, polyunsaturated and trans fats.

Click Here for a Kahn Academy Video Tutorial on Saturated-, Unsaturated-, and Trans-Fats

(Note: All Khan Academy content is available for free using CC-BY-NC-SA licensing at www.khanacademy.org )

Key Factors for Determining Cis/Trans Isomerization

- The compound needs to contain a double or triple bond, or have a ring structure that will not allow free rotation around the carbon-carbon bond.

- The compound needs to have two non-identical groups attached to each carbon involved in the carbon-carbon double or triple bond.

(Back to the Top)

E-Z Nomenclature

The situation becomes more complex when there are 4 different groups attached to the carbon atoms involved in the formation of the double bond. The cis-trans naming system cannot be used in this case, because there is no reference to which groups are being described by the nomenclature. For example, in the molecule below, you could say that the chlorine is trans to the bromine group, or you could say the chlorine is cis to the methyl (CH3) group. Thus, simply writing cis or trans in this case does not clearly delineate the spatial orientation of the groups in relation to the double bond.

Naming the different stereoisomers formed in this situation, requires knowledge of the priority rules. Recall from chapter 5 that in the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority system, the groups that are attached to the chiral carbon are given priority based on their atomic number (Z). Atoms with higher atomic number (more protons) are given higher priority (i.e. S > P > O > N > C > H). For this nomenclature system the designations of (Z) and (E) are used instead of the cis/trans system. (E) comes from the German word entgegen, or opposite. Thus, when the higher priority groups are on the opposite side of the double bond, the bond is said to be in the (E) conformation. (Z), on the other hand, comes from the German word zusammen, or together. Thus, when the higher priority groups are on the same side of the double bond, the bond is said to be in the (Z) conformation. Figure 8.14 shows the steps used in assigning the (E) or (Z) conformations of a molecule.

Figure 8.14 Steps used to assign the (E) and (Z) Conformations.

Click Here for a Kahn Academy Video Tutorial on E/Z Isomerization.

(Note: All Khan Academy content is available for free using CC-BY-NC-SA licensing at www.khanacademy.org )